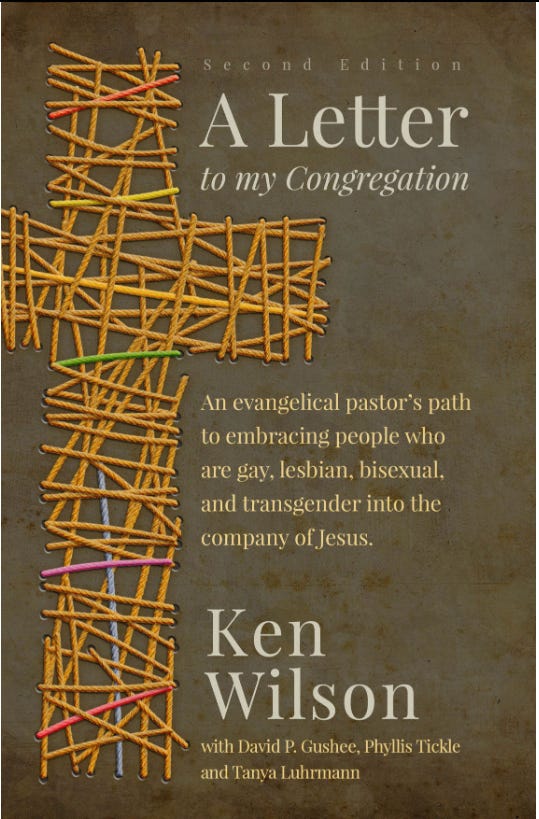

Just To Review: My Response to Preston Sprinkle's Review of "A Letter to my Congregation" by Ken Wilson

Some Background: Preston Sprinkle’s latest book is set to drop on August 1st. It is a list of Sprinkle’s responses to 21 arguments in favor of same-sex marriage. I very much intend to review Sprinkle’s book but I realized that I ought to re-publish my original response to his review of Ken Wilson’s book “A Letter to my Congregation” in advance since he has already indicated that one of the arguments he responds to in the book will be the thesis of Ken’s book. Since that conversation has already taken place I thought that this could be worthwhile pre-reading. Obviously I have no idea whether or to what degree Preston has updated his argument since 2015 but he did recently cite Ken Wilson on this argument when he previewed his book last week.

Please do keep in mind that I wrote this in 2015 and, of course, several things have changed in the intervening years. I recognized my own identity as a transgender woman and a lesbian, I read and learned a great deal more about fascism, and watched in horror as the white evangelical church came to openly embrace white Christian Nationalism, and I continued to interact with Preston Sprinkle (on Twitter, through his podcast, books, and blog) sufficiently to have now, with regret, become far more cautious regarding Sprinkle’s use of niceness in his writing (My extended review of “Embodied” his book about transgender people is available on this blog—the first installment can be found HERE). Sprinkle’s original review of Wilson’s book was published to his Patheos Blog and maybe found here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

My original response was published in two parts and I have combined them here.

Part 1

Dr. Preston Sprinkle has written a three part review of A Letter to my Congregation and it is, in many ways, a remarkably gracious review. Dr. Sprinkle goes out of his way to affirm Ken Wilson’s heart and faith and throughout the review he maintains a courteous, even warm tone. To be sure, while he appreciates the heart, goal, and tone of ALtmC, he disagrees with much of its argumentation and content. But his disagreement is both respectful and (mostly) clearly stated. Dr. Sprinkle is exactly the sort of person you would want to have a disagreement with. He neither raises his “voice”, nor resorts to the ad hominem attacks which have become so unfortunately common in the Church’s contemporary conversation.

His review of the book is divided roughly into what he really appreciated about ALtmC and some hesitations about the its characterization of traditionalist Christians (the first post), a three point critique of the book’s historical defense of a fully inclusive exegesis (the second post), and a theological critique of the book’s fundamental “third-way” thesis (the third post). So far as I can tell, the real sting of Dr. Sprinkle’s critique comes in two forms: historical and theological. In the second and third points of the second post Dr. Sprinkle challenges Ken Wilson’s historical research into the existence and prevalence, in the first century, of monogamous same-sex relationship which avoid temple prostitution, slave rape, and pederasty. In the third post he offers a theological critique suggesting that the third-way interpretation of Romans 14 cannot apply to homosexuality in the modern church on the grounds that the issues (eating meat sacrificed to idols and the observance of holy days) Paul addresses in Romans 14 were not “serious moral matters”. I intend to address the historical critique in this post and the theological in the next.

CRITIQUE OF SPRINKLE’S HISTORICAL CRITIQUE

Sprinkle’s historical critique is the focus of points 2 and 3 in Part 2 of his review, and I think that he makes two distinct mistakes in it. First, Sprinkle first grants and then challenges the book’s central claim so that it is difficult to tell what, specifically, he is pushing back against. Second, Sprinkle presents his historical counterexamples as definitive when they are actually subjects of significant scholarly debate.

Let’s lay it out. In ALtmC, the claim is that pederasty, slave-rape, and temple prostitution were the dominant expressions of homosexuality in the 1st century Roman world, saying, in effect, that those expressions, those actions, are what people would have been thinking of when they talked or thought about men having sex with men, or women having sex with women. ALtmC concludes that, since those practices were characteristic of the same-gender sex known in the ancient world and not the focus of the church’s dispute in the modern world, it is an exegetical mistake to see Paul’s language in Romans 1, 1 Corinthians 6, and 1 Timothy 1 as automatically and indisputably condemning the committed, monogamous, and loving on-abusive same- encounter today.

Dr. Sprinkle grants this claim writing directly to Ken Wilson, saying “Second, you argued that the main forms of same-sex relations in the Greco-Roman world were temple prostitution, pederasty, and sex with slaves. This is actually correct. According to the literature (more on that below), these were the main forms” but goes on to criticize ALtmC for identifying only two potential counterexamples to his claim (The Emperor Nero’s “marriage” to Sporus, and a passage from Plato’s Symposium). Sprinkle grants again that these are terrible counterexamples but claims that ALtmC has failed to recognize that there are “many others more legitimate examples” and then lists some of the “more legitimate examples” he is thinking of, promising that his upcoming book will provide a greater catalogue.

But if Dr. Sprinkle thinks that ultimately ALtmC is correct in its assertion re: temple prostitution, pederasty and slave rape, why is he so bothered by its failure to mention more than a few potential contrary pieces of evidence. It seems a bit like two people agreeing that it is a good idea to walk to the park and then one spending several minutes explaining that the other hadn’t really thought the decision through sufficiently. The explanation may or may not be a good one, but it is difficult to see why it is relevant. So too, if Sprinkle thinks that ALtmC does not give enough weight to counter examples, then why is he willing to grant the overall claim?

His third historical critique in Part 2 of the review is built on the assumption that ALtmC has failed to demonstrate that these harmful practices were the dominant expressions of homosexuality and then sneaks in the assumed conclusion that Romans 1 is not directed primarily at them. Thus Dr. Sprinkle seems to have his cake (granting a valid historical argument in ALtmC) and eat it too (denying the validity of the same argument based on evidence he supplies). Either his evidence is sufficient to overturn the conclusion--in which case Dr. Sprinkle should not have granted it--or it is insufficient--in which case it is a perfectly legitimate basis for the book’s conclusions about the implications of Romans 1.

CRITIQUE OF DR. SPRINKLE’S EVIDENCE

But let’s suppose for a moment that Dr. Sprinkle had not granted the point and that he contends (as some others do) that committed, monogamous, non-abusive same-sex relationships were as much a part of the 1st century Roman conceptualization of homosexuality as they are today, or at least, that they were common enough that Paul would have had them in mind when writing Romans. In fact the historical counterexamples Sprinkle provides do not clearly support this view. Of course I don’t know which examples Sprinkle has in his book (it won’t be released till December) but the examples he provides (presumably those he thinks are strongest) are:

Hippothous and Hyeranthes from An Ephesian Tale, by Xenophon

Some men from Leucippe and Clitophon by Achilles Tatius (I suspect he is referring to either Clineas/Kleinias and his lover, or Menelaus and his lover but Sprinkle doesn’t specify),

Encolpius and Ascyltos from the Satyricon by Petronius,

Berenike/Berenice and Mesopotamia in an account by Iamblichos,

Megilla and Demonassa in Lucian’s Dialogues of the Courtesans

Clement of Alexandria’s reference to woman-woman marriages

Ptolemy of Alexandria’s reference to women taking “lawful wives”

Two Jewish documents condemning women marriages

A funeral relief depicting two women holding hands in the manner of married couples.

Some scholars (notably Bernadette Brooten) hold that these are effective evidence that consensual, monogamous, non-abusive same-sex relationships (and possibly marriages) were sufficiently commonplace in the 1st century Roman world that they would have been a significant part of the general public’s conception of homosexuality. The problem is that Dr. Sprinkle presents these examples as if they were clear and determinative evidence where in fact they are shot through with problems. An Ephesian Tale and Leucippe and Clitophon are actually works of fiction (which Dr. Sprinkle acknowledges) and both post-date the writing of Romans by at least 50 years (closer to 100 years in the case of An Ephesian Tale) which makes them a poor source for anyone who wants to discover the cultural views of the mid 1st century Roman world. Furthermore Leucippe and Clitophon does not make it at all clear that either of the relationships it discusses were not actually pederastic. The Satyricon is late 1st century and therefore also somewhat anachronistic in this context, but is also wholly unsuitable for this sort of a claim given that Encolpius spends a good portion of the story fighting with Ascyltos over which of them will be the regular lover of the slave boy Giton. Whatever the relationship between Encolpius and Ascyltos, it is clear from the text that they were far from committed or monogamous.

The remaining examples, Dr. Sprinkle seems to have found in Bernadette Brooten’s book Love Between Women: Early Christian Responses to Female Homoeroticism. Brooten is a fine scholar but it is problematic that Dr. Sprinkle presents evidence from her work as though it were uncontested without recognizing the major critique of her claims by major scholars in the field, notably David Halperin and Alan Cameron. Cameron points out in his own review of Brooten’s book that the word married (γαμειν) in Clement was (at the time he was writing) a fairly common euphemism for “had sex with”. Clement uses the word to describe Aphrodite’s action towards Anchises (she mates with him, she certainly didn’t marry him) and when he uses it of female homoeroticism he says that women “play the male role, getting married and marrying women contrary to nature". Cameron points out that if Clement is referring to a permanent union, it makes no sense for him to repeat the word “marriage” in both passive (“getting married”) and active (“marrying”) forms. But that construction makes perfect sense if Clement is describing lesbians taking the “masculine” and “feminine” roles in sex--a distinction which was incredibly important to people of the period.

The example from Ptolemy is even more problematic as evidence. Cameron accuses Brooten of omitting the crucial term “as though” (ὥσπερ) from her paraphrase of Ptolemy, thereby changing “the women with whom they are on such terms as though they were actually their legal wives" “women…whom they call their 'lawful wives.". So contrary to Dr. Sprinkle’s assertion, Ptolemy did not say that women took lawful wives.

Dr. Sprinkle’s reference to “Two Jewish documents that were written shortly after the New Testament refer to (and forbid) female marriages that were happening in their day” is particularly difficult since he declined to name the documents. Given that all of the other items in the paragraph are derived from Brooten’s Love Between Women it seems likely that he is referring to The Sentences of Pseudo-Phocylides and the Sifra which are the two sources she mentions in that context. If so (and I know of no other potential sources of this type) he is on extremely thin ice. Brooten herself comments that Pseudo-Phocylides may actually be referring to a woman taking the “masculine” role in a heterosexual marriage (in footnote 152) and that the Sifra may see women-women marriages as bizarre fictions rather than realities of which any of its authors were aware (p.70) So Brooten herself concedes that these sources (if they are the ones Dr. Sprinkle is referencing) are disputable as evidence of same-sex marriage relationships.

In his citation of the funeral relief Dr. Sprinkle describes as “two women are holding hands in a way that resembles ‘the classic gesture of ancient Roman married couples’”. Brooten is less certain than Dr. Sprinkle, noting that a marriage relationship between the two women is only one of a number of possible interpretations of the relief and she cites as her source, a paper titled Women Partners in the New Testament, by Mary Rose D'Angelo which (when I looked it up) adds the caveat that the handclasp in the relief is “frequently (but not exclusively) used to depict the marriage bond. So D’Angelo’s “frequently (but not exclusively) becomes Brooten’s “one possible explanation” becomes Dr. Sprinkle’s bolded “resembles ‘the classic gesture of ancient Roman married couples”. This effectively illustrates what I found to be so troubling about Dr. Sprinkle’s “evidence”. The sources he cites certainly do exist, but on close inspection they all turn out to be far more complicated and far less unambiguously supportive of his conclusion than Dr. Sprinkle presents them. A reader who did not take time to research Dr. Sprinkle’s sources would likely come to the completely mistaken impression that these examples are straightforward open-and-shut cases of committed, monogamous, non-abusive same sex relationships, where the reality could hardly be further from the truth.

CONCLUSION

Ultimately the historical claims in A Letter to my Congregation stand on solid historical grounds. While it is certainly worth mentioning the fact that some scholars (most notably Dr. Brooten but Robert Gagnon and some others as well) contest those claims, many (Sarah Ruden, Alan Cameron, Louis Crompton, and David Halperin to name a few) support them. And, tellingly, that echoes the book’s thesis. This really is a disputable matter.

In the next part of this series, I will address Dr. Sprinkle’s theological critique of A Letter to my Congregation.

Part 2

In Part 1 of this series I responded rather critically to the historical claims in Part 2 of Dr. Preston Sprinkle’s 3 Part Review of Ken Wilson’s A Letter to my Congregation. In this post, I will be responding to Dr. Sprinkle’s theological critiques in Part 3 of his review. As in the last post, I have little positive to say about the substance of Dr. Sprinkle’s review so I want to begin by appreciating his approach. Dr. Sprinkle writes with both grace and love, and gives every impression of a brother in Christ who, despite some serious disagreement, genuinely respects Ken Wilson and his project in ALtmC. Such respect for and grace towards those with whom we disagree is a rare commodity in the internet age and very much appreciate this review for its consistently generous tone and approach.

Dr. Sprinkle’s theological or, maybe more accurately, exegetical critique of ALtmC seems to boil down to three claims in Part 3 of his review. First, he questions the claim that Paul saw as serious moral matters the choice to eat or refrain from meat which had been sacrificed to idols, and observance or ignoring of special holy days. Instead Dr. Sprinkle suggests that while these might have been of great moral concern to the Roman church, they were actually of fairly little concern to Paul. For Dr. Sprinkle this would suggest that the principles in Romans 14 would not map on to the Church’s contemporary disagreement over the full inclusion of LGBT persons. Second Dr. Sprinkle suggests (conceding the first point for the sake of argument) that if those who support full inclusion for LGBT persons map on to the stronger brother in Romans, then their responsibility is to refrain from performing or practicing same-sex marriages out of regard for their weaker brothers (those who believe God prohibits all gay sex). Finally, Dr. Sprinkle suggests that ALtmC, while correct in pointing out evangelical inconsistency regarding remarriage after divorce, errs in concluding that evangelical acceptance of re-marriage ought to justify evangelical acceptance of full inclusion for LGBT people, and that instead evangelicals may have a duty to re-fortify their lines against remarriage after divorce.

The first critique that, unlike his audience Paul would not have seen the Romans 14 issues as morally important, struck me as novel. Others may agree on this, but it is not a position I have run across before and I found myself reacting in a number of ways. First I am not sure why Dr. Sprinkle needs to make the distinction. If we are going to apply Romans 14 to our own lives, then surely we should identify with the “weaker brothers” in the Roman church who, by Dr. Sprinkles own admission, must have seen the issues as morally important. There doesn’t seem to be any reason to write a letter about an issue none of the audience thinks is important. If Christians are going to apply Romans 14 at all, doesn’t it have to be to issues we think important as well as those we think unimportant? If nobody is able to identify as the “weaker brother” in any given dispute, then Paul’s Romans 14 solution makes no sense. Rather than a “weaker brother” and a “stronger brother” each dispute will consist of a “faithful interpreter” and a “stronger brother” and will be proof against Paul’s resolution. It seems to me that until we can look at something and say “I am pretty confident that is sinful” and still admit that we may be the weaker brother, unless we are willing to risk being wrong about matters that we perceive to be first order moral concerns, we will be unable to apply a Romans 14 solution to our disputes with fellow believers.

And I don’t think that Dr. Sprinkle is on particularly solid biblical ground when he questions whether Paul himself saw this as an important moral issue. In Galatians 4:9-11, after thoroughly berating the Galatians for clinging to the “works of the law” rather than to faith in Christ, Paul says “But now that you know God—or rather are known by God—how is it that you are turning back to those weak and miserable forces? Do you wish to be enslaved by them all over again? You are observing special days and months and seasons and years! I fear for you, that somehow I have wasted my efforts on you.” (New International Version, emphasis mine). Clearly the observance of holy days was something Paul felt was, at the very least, a portion of an error so great that it risked turning Paul’s evangelism into a waste of effort - hardly a minor issue then.

He ends this line of thinking by observing that “same-sex relations were unanimously prohibited in Judaism, the NT, and early Christianity.” and concluding that those communities did not debate full inclusion for LGBT folk. Of course he is correct that (so far as we know) people did not debate that question in the first century, but Dr. Sprinkle seems to have completely missed the point here. The point is that the principles found in Romans 14, are applicable to the contemporary division over LGBT inclusion, not that Romans 14 is somehow directly discussing that situation. After all, one of the great glories of the Bible is that it provides principles which remain applicable even when the specific circumstances which those principles first addressed are no longer in place. And the principles of Romans 14 remain eminently relevant to our contemporary disagreements.

Dr. Sprinkle’s second suggestion is that if the contemporary church division over the full inclusion of LGBT people does map onto the issues Paul is addressing in Romans 14, then the responsibility of the “stronger brothers” is to refrain from practices which might cause the “weaker brothers” to sin by violating their own consciences. He specifically suggests that “if the affirming gay believer parallels the “strong” believer, and the non-affirming believer parallels the “weak,” then according to Ken’s logic the gay believer should avoid a same-sex marriage relationship for the sake of not offending the weaker believer.” This objection or question also strikes me as rather strange. Romans 14 certainly does contain commands that the stronger brother abstain from practices which might damage the faith of the weaker, but it also commands that the weaker brother abstain from judging the practices of the stronger. This does present legitimate challenges to those of us who support full inclusion of LGBT Christians in the church. We are challenged not to push people beyond what their conscience will allow. We are not to force our non-inclusive siblings to participate in what they see as sinful. But so too, they must refrain from judging or restricting their LGBT siblings when those siblings are acting out of their love for Christ and their neighbors.

In his third question/critique, Dr. Sprinkle takes significant space to appreciate the real disparity between the evangelical church’s treatment of Divorce and remarriage and its treatment of same-sex marriage and full LGBT inclusion. But he suggests that the solution to this disparity is that the church ought to become more strict in dealing with divorced and remarried people (he refers to this as the “plank in our own eye”). If the point in the ALtmC’s reference to divorce were a simple “these issues should be treated equally”, this might be a legitimate recommendation. But that isn’t the point. The church’s recent shift on divorce and remarriage is relevant to the conversation about same-sex marriage and full LGBT inclusion because it illustrates our capacity to implement a Romans 14 third way approach when the issue we are dealing with is not a key “battleground” in the culture war. The reference to divorce and remarriage in ALtmC is a call to Christians to recognize that we are capable of genuine Romans 14 behavior and that maybe our reasons for not doing so now are more tied to our cultural milieu than to our fidelity to Scripture. We have already learned to implement Romans 14 third way approaches in the Church, what’s lacking now is simply our will to apply them to our LGBT siblings.

But I want to end in the same spirit Dr. Sprinkle ended his review. Despite disagreements which I think are poorly founded, Dr. Sprinkle stands out in this conversation as an incredibly gracious reviewer. He ends the series acknowledging disagreements but looking for common ground. He cheers for the goals of ALtmC and he admits to being challenged by those parts of it he disagrees with. Dr. Sprinkle is clearly a man trying to love his neighbor and his Church and I look forward to reading his thoughts and opinions on the topic when his book comes out in December. Maybe I’ll review it.